How Shivaji Park evolved

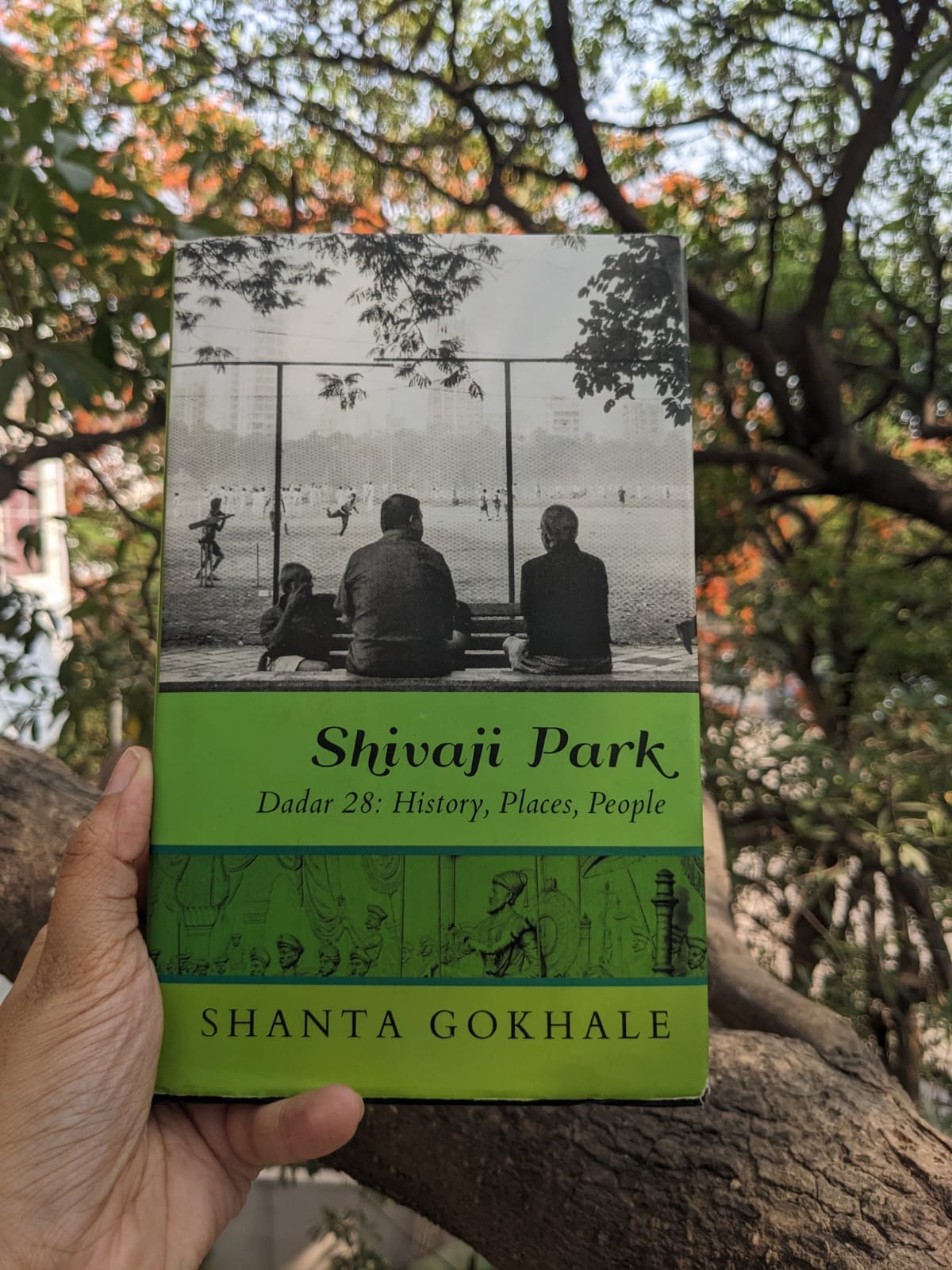

Shivaji Park is a story of urban design, modernity of art deco buildings, and a community that thrives in its open spaces.

Places look back at people. They have a gaze of amusement, and a voice that says, "you've been here before, yet you see, only now". Shivaji Park is the place, I am the visitor who has started to see it for the place it is, only now.

In a week’s time I made it to Shivaji Park, thrice. These repeated instances, helped me look at Shivaji Park like I had never before. And since, my thoughts are a storm in a tea cup.

On paper, Shivaji Park came into being around 1915 in an town plan made by the Bombay City Improvement Trust in the wake of a plague outbreak in 1896. Earlier, the land had a history of a complex and free village common. The urban plan crafted Shivaji Park into 28 acres or 16 football grounds of land. The town plan was a shade different from what urban plans are known to be. Instead of a sq. meter by sq. meter detail of land use, zone separations, and management of building forms, it was a simpler plan of allocation, and division of responsibilities between the improvement trust and the municipal corporation. It’s scale confined to a neighbourhood, not a region or a metropolitan.

Streets, drains, and light were created by engineers with local knowledge under the turf of the Bombay City Improvement Trust, an agency created by an Act of British Parliament. Allocation of plots to build, and regulations for buildings to follow, were in the care of the local Municipal Corporation.

The grids that composed Shivaji Park were a natural boundary laid out by existing roads. Lady Jamshedji road connecting Mahim causeway to South Bombay became it’s eastern boundary, Arabian sea, the western boundary. Ranade road was the southern boundary where an amoeba like fission took place to gave birth to Shivaji Park. The public ground in the centre was reserved away from any built form and the only lines drawn were circles, like two ripple rings, around it. About 200 plots were cut between the two rings, and allocated to build houses to anyone who bid for it. Lo and behold, that’s how the neighbourhood was born!

The park is a large carpet tying the neighbourhood together. It is also it’s living room with no boundaries. It is open to anyone, anytime. While parks in the rest of the city are separated by tall boundaries, Shivaji Park’s perimeter is lined by it’s katta, a low platform to sit on. The pavement alongside, grants pedestrians one delightful wish: The rhythm of a natural, uninterrupted walk. On this walk, clouds of thought, rain, and tunes of conversation, flow. None of this can be planned for. It’s a design that reflects the community’s choice and culture. Shivaji Park on my walks felt as much mine, as it is my friend's, who grew up here.

Another part of the neighbourhood, another day, I found myself walking in the company of my friends and parents of a fascinating six-year old. Walks in the company of kids are memorable. They remind you, how movements of a toddler are celebrations, even landmarks in time. These pavements are rarer for the buildings they line up to.

While walking, a remark shot across from me like a dart headed for the board: "These maybe the last few art deco buildings left in the city, worth admiring, while they last". Nothing hits the psyche more than the thought of disappearance of something you've just learnt about! "You've been here before, yet you see, only now", I hear my mind tell me, another time, as I set my eyes on the art deco buildings of Shivaji Park. These buildings, after it’s residents are main characters in a tale of the neighbourhood’s history.

Once upon a time, many years ago, reinforced concrete cement came into being. And architects deployed suave lines and round corners, to turn buildings into a vision of futuristic sea faring objects. It was possibly a renaissance like moment in the life of buildings of Bombay in the decade of 1910. Building regulations permitted that only a third of the plot could be built on, with building height permits allowing structures not more than ground + 2 floors, with a permission to add a third floor given away much later. These buildings shaped their residents as much as residents shaped them. Space plans contained toilets within buildings, something unheard of earlier.

Aged buildings are misunderstood as just relics of the past. They, in fact enable diversity in a neighbourhood that newly constructed high-rise towers don't. Thanks to their antiquity, the middle-middle, and the middle-lower income classes have places to stay and thrive among the better off. The art deco buildings are characters of grace influencing the diversity of Shivaji Park. Unfortunately, legislations, that influence their existence, may also have a hand in bringing them down. Rent control laws, poorly worded conservation laws, and lack of clarity in tenant-landlord rights and duties, are making it easy to erase them. Residents, are no longer able to resist redevelopment, even if they wish to.

If builder interest groups were birds, they are probably falcons. Clutching land parcels to build tall in Mumbai’s real estate market is tough. But builders are finding it easier to break norms, and persuade residents to give up their art deco buildings. Messy is also the fact that builders double up as politicians. What maybe prolonging the life and times of art deco buildings today are not efforts at conservation but delayed lawsuits that take decades to resolve in Indian courts. Every year or so, another one, bites the dust.

The story of Shivaji Park that spans a hundred years and more, makes it a precious neighbourhood. It’s gradual evolution is a case of town plans made their own by the ingenuity, diversity, and open-ness of its residents.

P.S. Great thanks to Ms Shaina Patel for her pictures of art deco buildings, the park katta, and her company that opened my eyes to her neighbourhood.